Why Standardised Dietary Approaches Show High Variability in Individual Outcomes

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

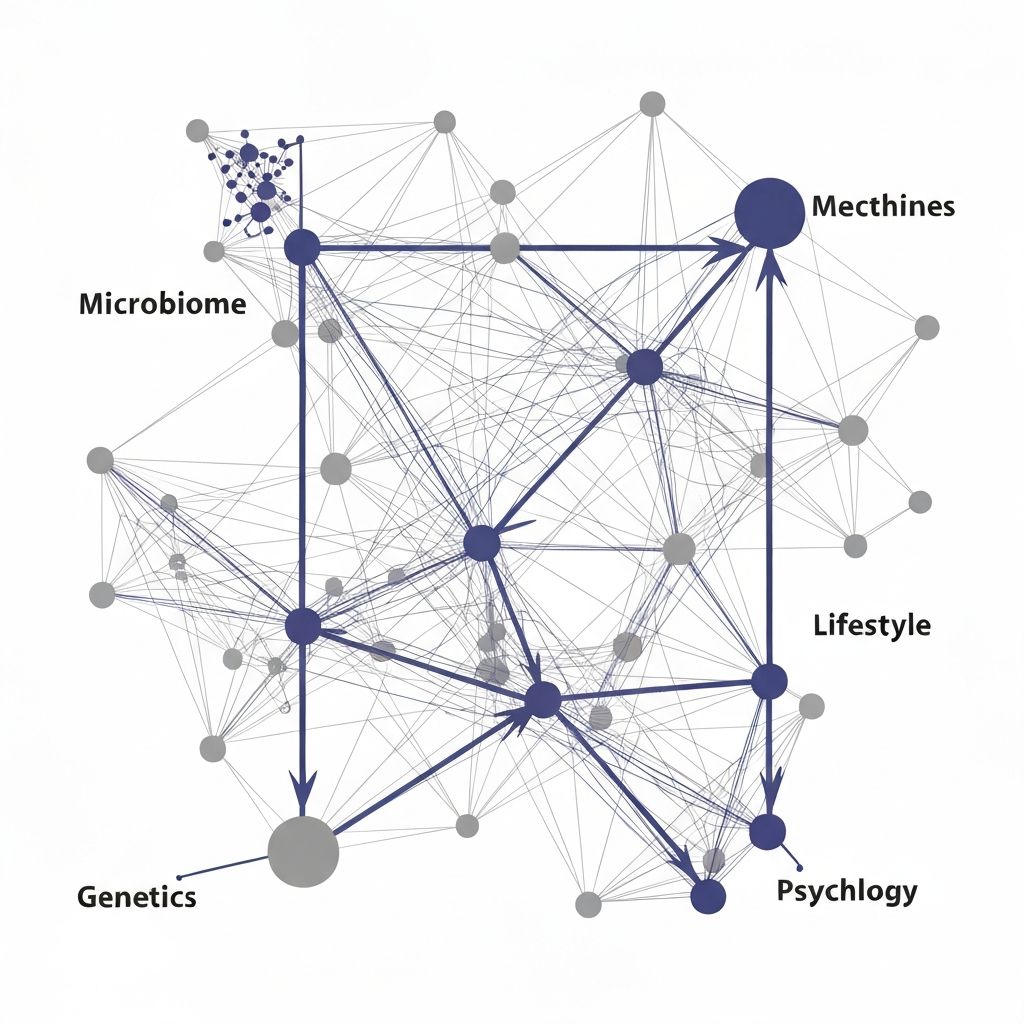

Inter-Individual Variability Concept

Standardised dietary interventions—protocols applied uniformly across populations—consistently demonstrate wide variation in individual outcomes. This is not a failure of study design, but a documented feature of human metabolic, hormonal, behavioural, and physiological responses to food.

Controlled clinical trials repeatedly show that identical dietary protocols produce markedly different results across participants. These differences are measurable, reproducible, and reflect genuine biological heterogeneity rather than compliance variations alone.

This educational resource examines the scientific evidence for inter-individual variability, the contributing factors documented in research, and how this reality is reflected in population-level dietary guidelines and nutritional science communications.

Key Contributing Factors

Genetics & Epigenetics

Genetic polymorphisms affecting nutrient metabolism, enzyme activity, and metabolic rate contribute to individual differences. Epigenetic modifications can alter how genes respond to dietary changes over time.

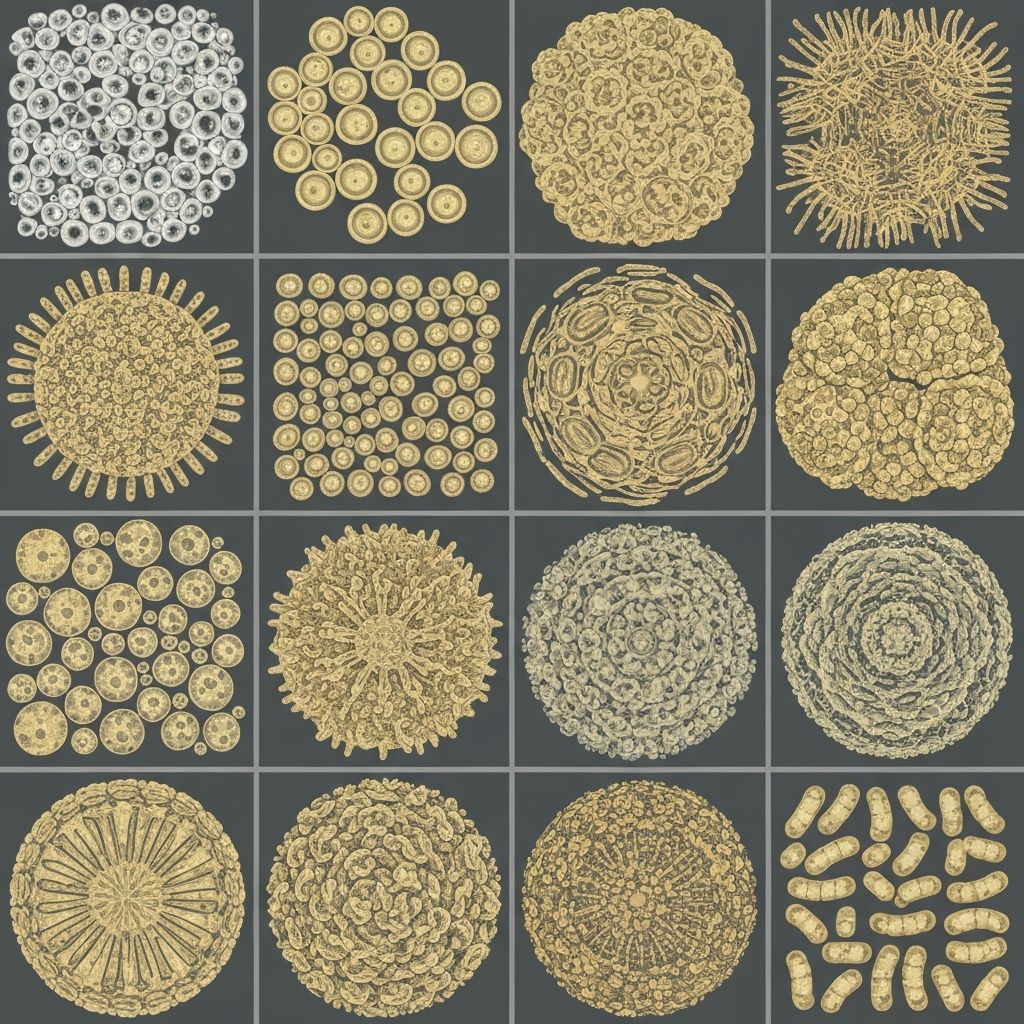

Gut Microbiome Composition

Microbial community diversity and structure vary substantially between individuals, influencing energy harvest, nutrient absorption, hormone metabolism, and metabolic endotoxemia production.

Lifestyle & Behavioural Factors

Physical activity patterns, sleep quality, stress levels, medication use, and baseline dietary habits all influence how the body responds to dietary change.

Psychological & Preference Traits

Individual taste preferences, food-related memories, cultural background, and psychological relationship with food shape both adherence and metabolic responsiveness.

Hormonal Status

Individual hormone profiles—including thyroid function, cortisol patterns, sex hormones, and insulin sensitivity—modulate metabolic responses to dietary composition.

Age & Metabolic Stage

Age-related changes in metabolic rate, digestive capacity, and nutrient absorption affect how different diets influence health outcomes across the lifespan.

Landmark Trial Examples

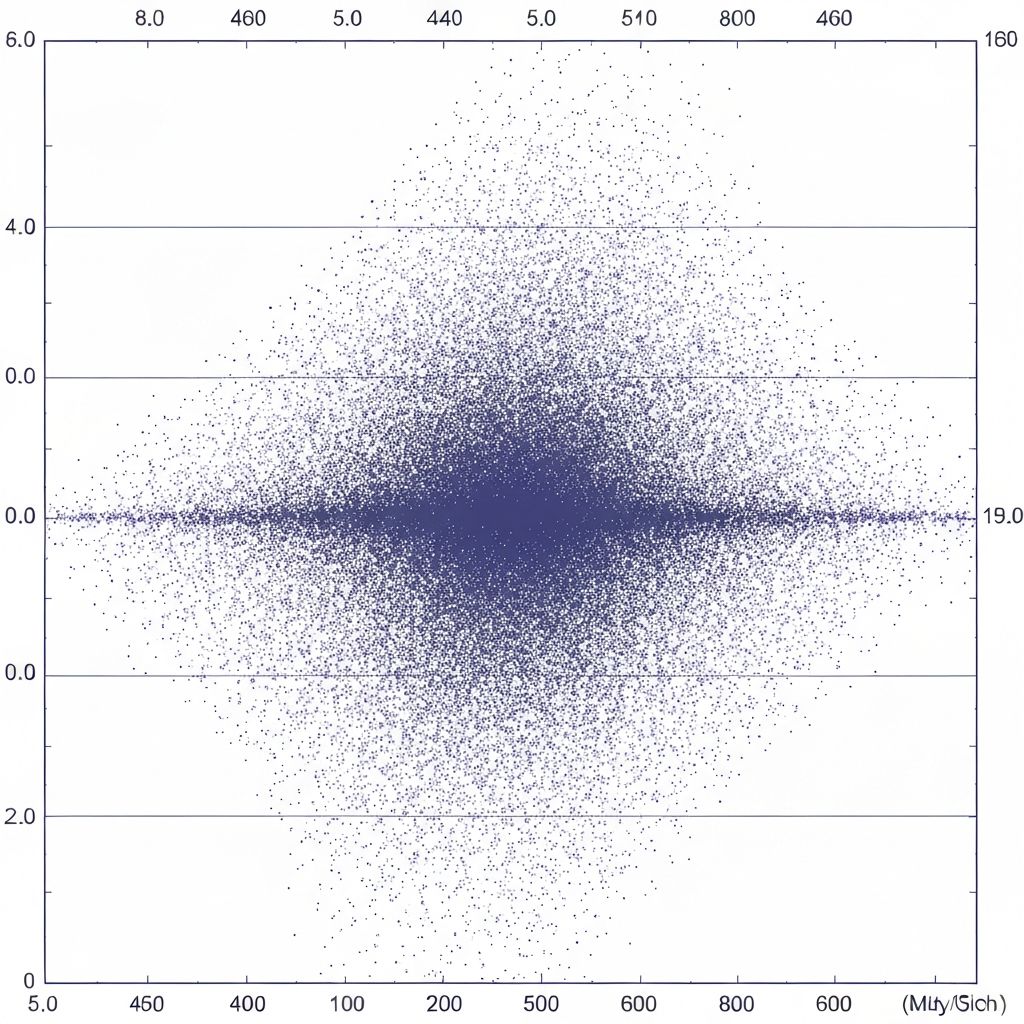

Large-scale randomised controlled trials designed to test standardised dietary interventions reveal substantial individual variation in outcomes. These trials employ rigorous methodology and careful monitoring, yet standard deviations in weight change, metabolic markers, and health indicators remain large relative to mean effects.

For example, major weight loss intervention trials often report average weight loss of 5–10 kg with standard deviations of 8–12 kg, meaning some participants lose substantially more, others lose less, and some gain weight despite protocol adherence. Similar heterogeneity appears in markers of metabolic health: cholesterol, triglycerides, blood glucose, and inflammatory markers.

This pattern is consistent across diverse dietary approaches—low-fat, low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, plant-based protocols—each showing substantial inter-individual variation in both efficacy and tolerability.

Adherence & Preference Patterns

Beyond biology, individual psychological and behavioural factors strongly influence dietary adherence. Observational cohort studies consistently show that adherence to any given diet varies widely, and long-term compliance is often the limiting factor in achieving sustained dietary change.

People respond differently to different dietary structures. Some thrive on frequent small meals, others on fewer, larger ones. Some find particular food restrictions motivating, others find them oppressive. These preferences are not simply psychological whims—they interact with metabolic processes and may influence overall dietary adherence and metabolic outcomes.

The variation in preference and sustainability patterns across populations means that a diet highly effective and easily followed by one person may be poorly tolerated by another, independent of metabolic factors.

Population-Level vs Individual Reality

Epidemiological research and cohort studies provide population-level averages: "Diet X is associated with Y health outcome." These averages are valuable for public health planning and understanding broad patterns. However, they describe group-level tendencies, not individual certainties.

An average effect of 0.5 kg weight loss on a standardised diet, for instance, masks the reality that within that population, some individuals lost 10 kg, others maintained, and some gained. The mean obscures the distribution.

Applying a population average effect directly to an individual—saying "this diet will lead to 0.5 kg loss for you"—commits an ecological fallacy. The individual's outcome depends on their unique biological, behavioural, and environmental context, which population-level statistics cannot capture.

UK Guideline Approach & Variability

UK public health dietary guidelines—such as the Eatwell Guide and NHS nutritional recommendations—are intentionally broad. This breadth exists precisely because individual responses to dietary composition vary widely, and one-size-fits-all specificity would be inappropriate.

Guidelines emphasise principles (varied vegetables, whole grains, adequate protein, limited sugar) rather than rigid meal plans or macronutrient targets, acknowledging that adherence and metabolic response vary between individuals. This evidence-informed flexibility reflects the scientific reality of inter-individual heterogeneity.

The guidelines do not promise specific weight loss or health outcomes for individuals, because such promises would ignore the documented variation in responses.

Research Limitations & Individual Prediction

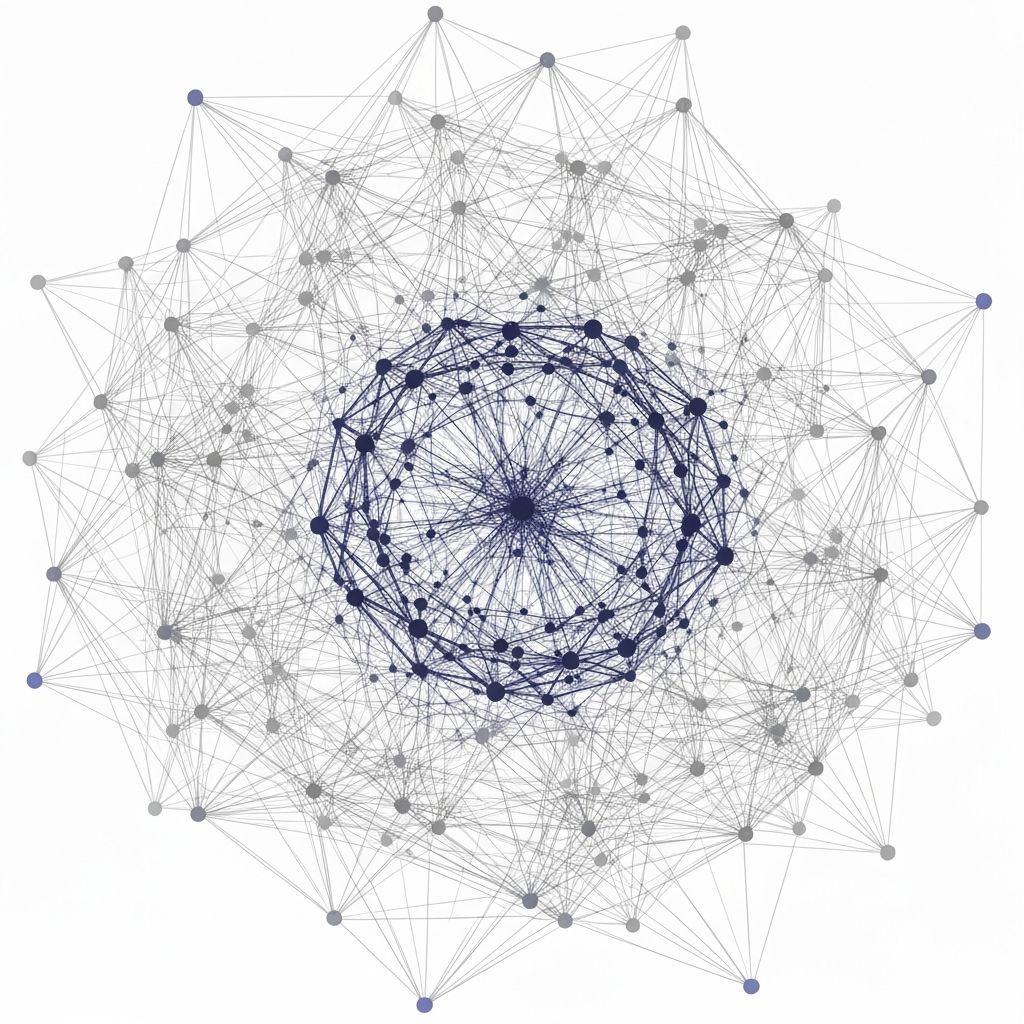

Current nutritional science cannot reliably predict which dietary approach will be optimal for a specific individual. Despite advances in genetics, microbiome analysis, and metabolic testing, the ability to forecast individual dietary response from baseline biological data remains limited.

This limitation is not a temporary gap awaiting future discovery—it reflects the true complexity of biological systems. Multiple biological systems interact (metabolism, hormones, microbiome, immune function, behaviour) in ways not fully captured by single markers or current testing modalities.

Research continues to refine understanding of variability mechanisms, but the practical implication remains: individual responses to dietary change can only be known through individual observation and experience, with professional guidance.

Broader Context: Total Lifestyle Beyond Diet

Individual outcomes depend not on diet alone, but on the interaction between diet and all other lifestyle factors. Physical activity, sleep, stress management, social connection, and overall life context influence metabolic health and weight independently and in interaction with diet.

Someone with excellent sleep, regular physical activity, and low stress may respond very differently to a dietary change than someone with poor sleep, sedentary habits, and chronic stress—even if the diet is identical.

This multi-factorial reality is why public health recommendations emphasise integrated lifestyle approaches rather than diet in isolation, and why individual professional guidance considers the whole person, not just dietary composition.

Observational Insights from Large Cohorts

Large longitudinal cohort studies tracking dietary intake and health outcomes over years demonstrate substantial diversity in trajectories. Two people with similar baseline characteristics and dietary patterns often experience different changes in weight, metabolic health, and disease outcomes over time.

These diverse trajectories illustrate that dietary response is shaped by complex, individual-specific factors. Identifying who will benefit most from a particular dietary approach, and who may not benefit or may experience difficulty, requires understanding the individual, not applying population-level generalisation.

Explore More

Article

Genetic Factors in Dietary Response Variability

How genetic polymorphisms and epigenetic modifications influence individual responses to standardised dietary interventions.

Read more

Article

Gut Microbiome Diversity and Nutrient Handling

The role of microbial community composition in metabolic heterogeneity and individual dietary responses.

Read more

Article

Behavioural & Psychological Influences on Adherence

How individual preferences, psychology, and behaviour shape dietary compliance and long-term outcomes.

Read more

Article

Wide Outcome Ranges in Landmark Diet Trials

Examining large standard deviations and heterogeneity in results from major randomised controlled dietary intervention studies.

Read more

Article

Population Guidelines and Individual Differences

How UK public health dietary recommendations account for variability and why they remain broad rather than prescriptive.

Read more

Article

Limitations in Predicting Individual Responses

Why current science cannot reliably forecast individual dietary response and what this means for personalised approaches.

Read more